Eleftherios (Terry) Soleas and Thomas Carey

In a previous post, we outlined a From Goals to Game Plans process we developed to help workplace partners identify the organizational priorities and ‘pain points’ shaping their goals in advancing workplace innovation (and complementing the employees’ goals around quality of work life). This process supports the goals of our research project on Workplace Innovation and Quality of Work: to curate research insights and exemplary practices in support partners’ efforts to advance workplace innovation by employees.

As a result of this process, one of our workplace partners asked for research insights to inform organizational plans to enhance employee motivation to innovate. That organization already has in place many supporting Organizational Capabilities, as highlighted in The Fifth Element model from Workplace Innovation Europe highlighted in previous posts.

Recent research by Terry has helped to clarify for us the factors that influence employee motivation to engage with workplace innovation [Soleas 2020, 2021]. This research adapted a common framework used for assessing motivation in the workplace [Flake et al 2015], and included an initial study with 30 recognized Canadian innovators as interviewees. The resulting prototype survey instrument was then iteratively refined in prototype tests with another 500 Canadians who had been identified as leading innovators in their workplaces.

This research also established reliability of the final Motivation to Innovate Inventory, which is now undergoing further tests to determine how it can best be used to develop innovation capability and to target organizational efforts to strengthen employee motivation to engage in workplace innovation. Those tests are adapting some of the subthemes identified by original interviewees concerning the influences shaping their experiences on each of these factors.

A Research-Informed Framework for a Targeted Research Synthesis

Terry’s research also suggests that developing stronger motivation for innovation requiresattention to a mix of factors: developing stronger employee Identity and Self-Efficacy as innovators and greater Value generated from innovation, while mitigating perceptions of the Costs of their participation in innovation (the one negative factor).

In the context of our Research Syntheses, this framework gave us a format to structure our presentation of research insights which could be adapted for the workplace partner’s context. In the longer term, an adapted Motivation to Innovate Inventory could potentially be used to identify particular motivational factors to be addressed with employees.

In what follows, we will illustrate how we have used these Motivation to Innovate insights as a framework to structure the research highlights we incorporated in our targeted research synthesis for the workplace partner described above. Each section explores research for potential adaptation from one of the first two factors identified above (with labels adapted to align with the results from that workplace partner’s From Goals to Game Plans process ):

Enhancing Self-Concept as an Innovator: Building Identity and Self-Efficacy

Innovation Process as Incentive: Engagement and Personal Development in Innovation

You can get a glimpse into the research adaptation process by comparing the language in these adapted titles with the titles from the original research reports as listed in the box above. Relative to our overall Research Project, we view our experience of adapting research insights to structure our presentation of potentially adaptable research insights by a partner as a novel meta-level example of “Results that Surprise” (a phrase emphasized to us as a reliable indicator of productive research by colleague and mentor Carl Bereiter at the University of Toronto).

Enhancing Self-Concept as an Innovator: Building Identity and Self-Efficacy

Engaging a broad range of employees in workplace innovation often requires reaching out to people whose initial conceptions of innovation – and of themselves as innovators – leads to ruling themselves out (“just not me”). In some workplaces, motivating particular innovation activities may also be assisted by innovation nudging [Stieler & Henike 2022] to support employees in building identity and confidence for themselves as innovators in those activities…

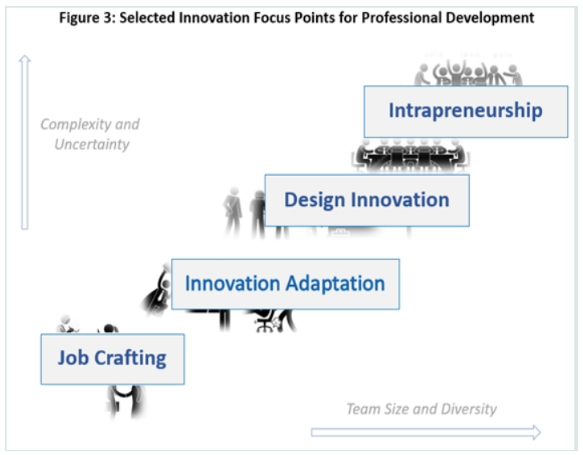

Research in Europe has shown that a progression of workplace innovation activities can begin with simple examples that such workers can easily relate to and see themselves taking on [Høyrup 2012]. Through a step-by-step progression, they can develop more confidence in their ability and identity as innovators, always with assurance that they will be the ones to decide their own comfort level in terms of the complexity and uncertainty they take on…

A previous post described how we developed the example progression shown in the figure in response to a case study with a previous workplace partner, where the innovation champions were struggling to fulfill for “every employee” engagement with workplace innovation The sequence begins with Job Crafting [Dutton & Wrzesniewski 2020], an exercise which has been undertaken by employees across a wide range of occupations – but not often positioned as a first step in engaging with workplace innovation. Further steps include Design Thinking as in Innovation Catalysts, a form of Design Innovation…

(We have also used this step-by-step progression to help both postsecondary students and working learners to develop their Self-Concept as Innovators and their Confidence in taking on Workplace Innovation activities.)

Innovation Process as an Incentive: Engagement and Personal Development in Innovation

One key incentive for employee engagement in workplace innovation is a rewarding personal experience with the work process of an innovation activity, including a mix of the following:

Enjoyment of the personal aspects of task processes

Sense of community from the social aspects of the process

Appreciation of personal contribution to the processes

Sense of accomplishment in developing personal capability

Employees’ innovativeness in organization can be enhanced by strengthening their sense of capability, community and appreciation. Monetary or non-monetary recognition can be used as supplementary motivators to advance idea-sharing. [Anttila 2021]

For example: regarding personal aspects of task engagement, contribution and capability development, each employee can be helped to focus on roles where they can contribute the most and achieve optimal satisfaction [e.g., Julian 2016; Liedtka et al 2022] by team leaders, catalysts and coaches. Leaders also facilitate a sense of community amongst team members.

The sense of accomplishment from personal capability development within a particular activity can also be enhanced through a “stackable” capabilities ladder, where the Skills and Knowledge for more complex, uncertain and impactful innovation activities explicitly build on the capability developed for simpler innovation activities with smaller teams [Nobis et al 2022].

The sense of accomplishment from workplace innovation is also heightened by continuing engagement in the work of innovation: Employee-led innovation can only happen in an rganization…if employers and managers empower the ordinary employees to not only generate creative ideas but also to participate in their development and implementation. [Echebiri et al 2020].

Employees also reference how their involvement in workplace innovation results in personal development that goes beyond the workplace: Going deep with design requires more than changing the activities of innovators; it involves creating the conditions that shape who they become. Individuals become design thinkers by experiencing design…Ultimately, innovators need to be someone new to create something new. [Liedtka et al 2021]

In a subsequent post, we will highlight other research insights from the remaining Factors:

3. Innovation Process as Incentive: Engagement and Personal Development in Innovation

4. Innovation Results as an (intrinsic) Incentive: Improving Employee Quality of Work Life

Including a section on What We Know about the role of Financial Incentives

5. Reducing Perceived Costs and Risks: Evaluating Innovation Processes and Outcomes

Acknowledgement: Our project on Workplace Innovation and Quality of Work Life is supported by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills program.

References:

References from the Introduction section on Factors that Influence Motivation for Workplace Innovation)

Flake, J.K., Barron, K.E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B.D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244.

Soleas, E. K. (2020). What Factors and Experiences Motivate Innovators? An Expectancy-Value-Cost Approach to Promoting Student Innovation (Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University, Canada).

Soleas, E. K. (2020). Leader strategies for motivating innovation in individuals: a systematic review. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 1-28.

Soleas, E. (2021). Environmental factors impacting the motivation to innovate: a systematic review. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 1-18.

References from Enhancing Self-Concept as an Innovator: Building Identity and Self-Efficacy

Carey, T., and Baregheh, A. (2019). “Every Employee” Engagement with Workplace Innovation: A Professional Development Ladder. Post in the WINCan.ca What We’re Learning weblog, July 27, 2021.

Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2020). What job crafting looks like. Harvard Business Review online.

Høyrup, S. (2012), “Employee-driven innovation: a new phenomenon, concept and mode of innovation”, in Høyrup, S., et al (Eds), Employee-driven Innovation: A New Approach, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp. 3-33

Stieler, M., & Henike, T. (2022). Innovation nudging—A novel approach to foster innovation engagement in an incumbent company. Creativity and Innovation Management, 31(1), 35-48.

References from Innovation Process as an Incentive: Engagement and Personal Development

Anttila, H. (2021). Capturing innovativeness of employees through ideation contests. Master’s thesis, LUT University

Echebiri, C., Amundsen, S., & Engen, M. (2020). Linking structural empowerment to employee-driven innovation: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Administrative sciences, 10(3), 42.

Julian, T. (2016). Roles Table in the “Encourage Every Employee To Play A Role” section of A Guide To Changing The Innovation Climate In Your Organisation. Hargraves Institute, Cammeray NSW Australia. p. 11.

Liedtka, J., Billing, A., Eldridge, J., Hold, K., Kuhne, B., & Tong, E. (2022). Assessing and developing an organization’s innovation competency profile. Strategy & Leadership, 50 (6), pp. 27-32.

Liedtka, J., Hold, K., & Eldridge, J. (2021). Part Four: Different Strokes for Different Folks. In Experiencing design: The innovator’s journey. Columbia University Press.

Nobis, F., Stevenson, M. Baregheh, A., and T. Carey (2022). Engaging Students with an Adaptable Model for Workplace Innovation Capability. In Case Stories: Innovation & Entrepreneurship Teaching Excellence Awards 2022.

About the authors

Eleftherios (Terry) Soleas is Director of Continuing Professional Development in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Queen’s University. The research described in this post was part of his Ph.D. thesis in Queen’s Faculty of Education.

Thomas Carey is co-Principal Catalyst (Academic Partnerships) with the Workplace Innovation Network for Canada, and a former Professor and Associate Vice-President at the University of Waterloo.