Thomas Carey and Eleftherios (Terry) Soleas

In a previous post, we summarized recent research by Terry that we have been applying with one of our workplace partners in our current research project on Workplace Innovation for Quality of Work (supported by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills Centre).

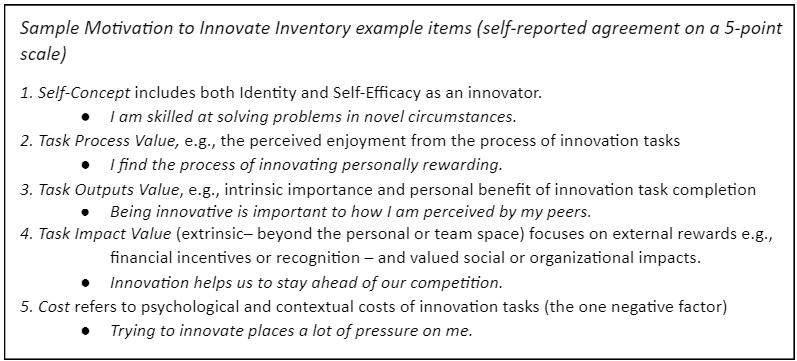

As described in that previous post, Terry’s research suggests that developing stronger motivation for innovation requires attention to a mix of factors: developing stronger employee Identity and Self-Efficacy as innovators and greater Value generated from innovation, while mitigating perceptions of the Costs of their participation in innovation (the one negative factor).

In Part I of this two-part post, we explained how we used the five factors identified in Terry’s research to structure a Research Synthesis we developed for one of our workplace partners, to guide their exploration of factors they might address with their employees to broaden and deepen motivation for innovation. We also shared some of the research insights which could be adapted to inform these joint employer-employee actions, focusing on the first two factors summarized in the Table below.

In this post, we will present similar reflections re research insights on the remaining three Motivation to Innovate factors identified:

Innovation Results as an (intrinsic) Incentive: Improving Employee Quality of Work Life

Extrinsic Incentives: What is the role of financial or other incentives?

Reducing the Perceived Costs and Risks of Workplace Innovation

Innovation Results as an (intrinsic) Incentive: Improving Employee Quality of Work Life

Workplace innovation projects typically address problems that emerge in the course of everyday work as workers encounter conditions ‘on the ground’ that are complex, situated, and emergent. The knowledge of these problems is often tacit…deeply embedded in ‘street-knowledge’ and therefore difficult, costly, and time-consuming to transfer to individuals not engaged in the particular front-line practices…When employees experience these problem situations, they often do so personally and directly. This means that the primary incentive for employee innovation to overcome these problems will therefore typically be to benefit from using the solution themselves. [Hartmann & Hartmann 2020]

The European conception of Employee-led Workplace Innovation emphasizes these win-win outcomes for companies and people: high levels of economic performance, high quality of working life and a high skill equilibrium [Totterdill & Eyton 2021]. There is a significant body of evidence to indicate that workplaces can adopt practices which promote these multiple goals and that these transformed workplaces can provide mutual gains for employers and for employees. For example, a recent national study in Denmark [Lorenz & Holm 2021] found that The employee-level results show that when employees’ work activity involves learning and problem-solving in combination with control over their methods and pace of work, satisfaction tends to be higher and there is less stress in work.

(There are also other intrinsic incentives which can accrue to employees from innovation projects that go beyond the immediate impacts on their quality of work life, e.g., visibility within the organization and growth in personal networks [Flocco et al 2022].)

Flocco, N., Canterino, F., & Cagliano, R. (2022). To control or not to control: How to organize employee‐driven innovation. Creativity and Innovation Management. [excerpt from the non-monetary incentives column of Table 2 Design Choices, p. 6-7].

Hartmann, M. R., & Hartmann, R. K. (2020). Frontline innovation in times of crisis: Learning from the corona virus pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(4), 1092-1103.

Lorenz, E., & Holm, J. R. (2021). Work organisation, innovation and the quality of working life in Denmark. In Globalisation, New and Emerging Technologies, and Sustainable Development (pp. 169-188). Routledge. p. 185. See also Oeij, P. R., Preenen, P. T., & Dhondt, S. (2021). Workplace innovation as a process: Examples from Europe. In The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Innovation (pp. 199-221). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Totterdill, P., & Exton, R. (2021). Workplace Innovation in Practice: Experiences from the UK. In The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Innovation (pp. 57-78). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. p. 63.

Extrinsic Incentives: What Research insights about the role of financial or other incentives

Previous sections have demonstrated that extrinsic incentives are not a required or preferred option for increasing motivation for workplace innovation. Incentives such as monetary rewards may still contribute value in a workplace innovation strategy, provided we recognize the constraints and challenges such as the following:

Motivating “only through monetary rewards does not yield a strong response and seems to have only small effects on increasing motivation”. [Dehvari & Wenner 2020]. See also [Sanders et al 2018] who note that “a significant relationship between performance-based rewards and innovative behaviors was not found”.

“Supplementary compensation may only influence performance strongly for individuals who have high endorsement of money ethic. In contrast, extrinsic rewards such as money may also undermine employees’ intrinsic motivation for a task”. [Karin et al 2010]. See also [Weghorst 2021], who notes that “there can be a negative relationship between rewards and innovation when employees are already intrinsically motivated”.

Other individual – and cultural – differences such as “uncertainty avoidance” may also limit the impact of monetary incentives [Sanders et al 2018]

“While the implementation of performance-based rewards can encourage innovative behaviors, these effects will only be achieved when implemented and communicated clearly within a consistent and well-understood set of HR practices. Without these conditions, a significant relationship between performance-based rewards and innovative behaviors did not occur.” [Weghorst 2021].

There are also challenges in adapting extrinsic incentives such as performance bonuses (individual or collective) to the innovation context: employees need to be supported in thoughtfully undertaking projects with uncertain outcomes, where significant value can be derived by learning “what not to do” in a project which might otherwise be deemed “a failure”:

Attempting to empower employees by offering rewards based on performance can inhibit innovativeness…[however], the expectancy that innovation itself is rewarded – rather than performance – encourages innovative behavior. [Fernandez & Moldogaziev 2013]

Dehvari, S., & Wenner, M. (2020). Managing internal ideation: A Case study at Bengt Dahlgren. Stockholm AB. Master’s Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2013). Using employee empowerment to encourage innovative behavior in the public sector. Journal of public administration research and theory, 23(1), 155-187.

Karin, S., Matthijs, M., Nicole, T., Sandra, G., & Claudia, G. (2010). How to support innovative behaviour? The role of LMX and satisfaction with HR practices. Technology and investment, 2010.

Sanders, K., et al (2018). Performance‐based rewards and innovative behaviors. Human Resource Management, 57(6), 1455-1468.

Weghorst, E. E. (2021). EDI through an online suggestion system: The influence of HRM activities on the implementation of innovative ideas. Master's thesis, University of Twente.

Reducing the Perceived Costs and Risks of Workplace Innovation

The last point in the previous section – how the value of an innovation project may be evaluated and potentially rewarded – is also directly related to employee perceptions regarding the costs and risks involved in an innovation project. Two specific issues have been raised with us by workplace partners as potential sources of employee concern:

Perceptions about apparently ‘negative results’ during a workplace innovation process, e.g., when a key hypothesis for the current design approach is proven to be faulty

Perceptions about apparently ‘negative results’ concluding a workplace innovation process, e.g., when an innovation team’s pitch for resources to continue a project is declined (in favour of other teams’ pitches) or the project concludes without reaching the goals the innovation team had hoped for (“ we now know that our organization should not be pursuing this direction at this time”).

This first of these contexts for seemingly negative results during a workplace innovation process has been explored in numerous studies, although we find ourselves rewording their advice in order to avoid the connotations of “the F word” (‘Failure’). For example, one source with effective guidance for innovation team leaders frames the challenge in this awkward way:

Design-thinking approaches call on employees to repeatedly experience something they have historically tried to avoid: failure. The iterative prototyping and testing involved in these methods work best when they produce lots of negative results—outcomes that show what doesn’t work. But piling up seemingly unsuccessful outcomes is uncomfortable for most people. …Our research has identified three categories of practice that executives can use to lead design-thinking projects to success: leveraging empathy, encouraging divergence and navigating ambiguity, and rehearsing new futures. [Bason & Austin 2019]

Our own preference is to talk instead about “learning to be surprised” during an innovation process rather than “learning to fail”, borrowing language from the development of capability for reflective professional practice [Jordan 2010].

For the second context, seemingly negative results which conclude an innovation project before the team members have achieved what they had hoped, we found a surprising lack of research. There are some insights in the context of Strategic Innovation [O'connor et al 2018], where the staff within a Strategic Innovation group can take mutual credit for the successes of their group as a whole and accept that some of their initiatives can be expected to not fulfill their expected potential (otherwise, the group will be deemed to be unreasonably cautious).

However, in the case of employee-led workplace innovation there is seldom such strong team identification as contributors to a larger group achievement. We have heard concerns from leaders of workplace innovation initiatives that employees will “lose heart” if they have more than one unsuccessful pitch in the organization’s annual Design Challenge or if they devote time away from their normal work roles on successive projects which produce negative results which lead to an early winding-down (however valuable those may be to the organization, which has been saved from continuous investment in projects with poor returns). We have yet to find research to address this concern. Suggestions would be welcome…

Bason, C., & Austin, R. D. (2019). The right way to lead design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 97(2), 82-91.

Beghetto, R. A. (2021). My favorite failure: Using digital technology to facilitate creative learning and reconceptualize failure. TechTrends, 65(4), 606-614.

Jordan, S. (2010). Learning to be surprised: How to foster reflective practice in a high-reliability context. Management learning, 41(4), 391-413.

O'connor, G. C., Corbett, A. C., & Peters, L. S. (2018). Beyond the champion: institutionalizing innovation through people. Stanford University Press.

Perlich, A., von von Thienen, J., Wenzel, M., & Meinel, C. (2018). Learning from success and failure in healthcare innovation: The story of tele-board MED. Design thinking research: Making distinctions: collaboration versus cooperation, 327-345.

Von Thienen, J. P. A., Meinel, C., & Corazza, G. E. (2017). A short theory of failure. In Electronic Colloquium on Design Thinking Research (Vol. 17, pp. 1-5).

Acknowledgement: Our project on Workplace Innovation and Quality of Work Life is supported by the Government of Canada’s Future Skills program

About the authors

Thomas Carey is co-Principal Catalyst (Academic Partnerships) with the Workplace Innovation Network for Canada, and a former Professor and Associate Vice-President at the University of Waterloo.

Eleftherios Soleas is Director of Continuing Professional Development in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Queen’s University. The research described in this post was part of his Ph.D. thesis in Queen’s Faculty of Education.